Class. Grace. Humility. Diligence. Mastery with fallibility.

It’s rare to find someone in the public spotlight whom all four generations of my family like.

My 97-year-old grandfather and 72-year-old father liked Walter Cronkite and Walter Matthau; my 10-year-old son likes Walter the Farting Dog.

My grandfather and father like Sophia Loren; I like Sofia Vergara. My son likes knowing that Sofia is the capital of Bulgaria.

My grandfather likes Eminem, my son likes M&Ms.

You get the picture. We don’t always agree on our cultural icons. (I was kidding about Grandpa and Eminem. He’s more a Sophie Tucker fan (although here, she’s speaking more than singing, so maybe she and Eminem have more in common than often given credit for in all the literature…you know, all the scholarly work that’s been done comparing Sophie Tucker and Eminem).)

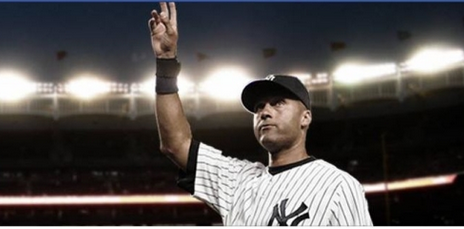

But Derek Jeter is different. First of all, I don’t believe he sings as well as Sophie Tucker or even Eminem, but I could be wrong. Jeter’s appeal transcends generations, and races, and every other group you can imagine. Others have written eloquently on this fascinating subject, way more eloquently than I. (To wit (a residual phrase from law school that I liked because it contained the word ‘wit’…then again, so dos nitwit), the great baseball writer’s Roger Angell’s tribute in The New Yorker.) This, like all my posts, is just a snapshot reflection, my perspective. I promise, I’m getting there…

It’s hard to write about Jeter without being hagiographic. All I want to show is deep respect.

In America, we love the underdog. We love building up the underdog. But when the underdog becomes the top dog, we often revel in tearing the poor (rich) pooch down.

We didn’t do that with Mr. Jeter. Because we don’t do that to true leaders, people whom we admire not for their fame, but for their ethic. Mr. Jeter is an example, not an embodiment, of the kind of person many of us strive to be, regardless of whether we’ve ever had 3,465 Major League hits, turned 1,408 double plays or won five World Series.

He had a dream as a child that he fulfilled because he busted his ass to make it happen. His parents believed in him and supported his efforts. He had coaches and mentors who saw his potential and helped him figure out what it would take to realize it. He seized opportunities presented to him and didn’t take them for granted.

He was fortunate to do something he truly loved, but being shortstop for the Yankees was his job, and he took it seriously. He famously acknowledged that he might not be the most gifted baseball player but that he would never be outworked. That was his source of pride, his motivator, his internum dynamismum. (I don’t even know if that’s a thing in Latin, I just like that Google Translate includes Latin. That was one of the only things I loved about law school was the chance to learn cool Latin phrases like “res ipsa loquitur,” inter alia.)

He was humble. When fans shouted their gratitude, he reciprocated by saying, “I don’t know why you’re thanking me. I should be thanking you. I was just doing my job.”

Mr Jeter approached every ground ball, however routine or challenging, with commitment and determination. Every at bat required mental acuity and physical prowess. He was prepared to do so because he practiced those skills hundreds of thousands of times throughout his life, both as an eager kid and a professional—beginning in his rookie season and throughout his 20-year Major League career.

He didn’t gloat or showboat—no chest-thumping, no post-play dance routines, no taunting the opposition. He was never thrown out of a game. He had too much respect for it. He never let his emotions get the better of him. He seemed to be well-regarded by teammates and foes alike, as was evidenced by the year of tributes and the Orioles’ sticking around to watch the outpouring of love from the Yankee faithful after they lost to Derek’s final hurrah, a game-winning, trademark opposite field single in the bottom of the 9th that thwarted one last possibility that the O’s could’ve snagged home-field advantage throughout the playoffs. Though the Yankees failed to make the playoffs this year, he tipped his cap to the O’s, complimenting them on how well they played and how they earned the American League East title, and wishing them well in the playoffs. Though he wanted that to be his last game at shortstop, he announced that he would still play in the final season series against the Yankees’ arch-rival, the Boston Red Sox, out of respect for the rivalry and the fans who already bought tickets.

How sad that such respect for the competition seems anachronistic, a quaint relic of a bygone, though by no means halcyon era. Congress, are you listening? Could you take a page from the Jeter playbook, working hard to do your job and to respect those on the opposite side of the aisle?

These are values that were readily practiced throughout the country and to which we still aspire. My grandfather learned them in over 40 years as a traveling salesman. (More on him in a future post.) My father learned them in over 25 years in corporate public relations. (More on him in a different future post.) It’s something I did as a student to excel in school and do what was expected of me (though not when it came time to pursue my own dreams).

I’m trying to instill those values in our son and daughter—that discipline and diligence are vital to success in any endeavor one pursues, whether it’s schoolwork, sports, the arts, jobs, relationships, passion projects. (More on all of this in future posts.) Thank you, Derek Jeter, for that reminder.

Baseball is a game of errors. He made 254 of them in his 20-year career. I made that many on my Crim Law final in a single afternoon first year of law school. He finished with an incredible .310 lifetime batting average, but that means he “failed” at the plate 69% of the time. That’s one of the things that makes baseball so incredible. It’s a game of resilience, not matter how often one “fails.” It’s the ability to restart that makes it, especially the way Mr. Jeter played it, so admirable. Maybe the number ‘2’ on his jersey was a reminder to all of us to keep striving—to persevere and improve no matter how many times we stumble. As another great athlete/human being, Pro Football Hall of Famer and the 1st African-American Supreme Court judge in the state of Wisconsin, Alan Page once said to me, “Success is in the strivin’, not the arrivin’.” (More on him in another post.)

What made Mr. Jeter such a great leader was simply setting a good example. His magnetism came from the respect that he earned, not fabricated, throughout the league by putting his head down and grinding it out every day. Every Dad (and Mom) in America could point to Derek Jeter and say, “That’s how it’s done.”

Back to the blog

Back to the blog Subscribe

Subscribe

Twitter

Twitter